Buckle up do-it-yourself rockers, because it’s rockabilly tow truck time! Yes, that’s right! DIYRockandRoll.com is proud to release its most requested project to date: an article on how to make an original rockabilly rave-up about a tow truck driver in Vermont. If you’re one of the legions of readers who requested that, read on, because the time has come!

A Brief and Subjective History of Rockabilly

But first: what is rockabilly? To answer that, let’s go back to a 1959 episode of Town Hall Party–an early television show that is sort of a spiritual descendent of the Grand Ole Opry and an antecedent to Austin City Limits.

The guest performer for the episode in question is rockabilly pioneer Eddie Cochran, then just twenty years old, and already coming off of genre-defining releases like Twenty Flight Rock, C’mon Everybody, and Summertime Blues. During a break in the music, Cochran and his band go up to the mic for an interview with the emcee–country music songwriter and performer Johnny Bond. Bond, clutching his Martin dreadnaught guitar and appologizing for the condition of his own tonsils, seems genuinely curious about Cochran and his music.

He asks, “Do you think that rock and roll is something new?”

“No I don’t, I really don’t,” Cochran replies, “I think it’s been around for a long time but nobody’s actually recognized it. . . . . rhythm and blues and blues, you know, and blues has been around for so long. And then they kind of blended country and western music in with it.”

It’s a thoughtful response, and a historically important one since it documents how one key rock innovator thought of the still-fledgling genre. But I do wish Bond had asked who the “they” were that Cochran referenced as doing the genre blending that created rock. That’s where things get really interesting and really complicated.

Arguably, some of the earliest rock and roll (likely the earliest) had little or no country music influence. Listen to seminal recordings like Fats Domino’s The Fat Man (1949) and Jackie Brenston’s Rocket 88 (1951)–both contenders for the first rock recording–and it’s hard to hear a heck of a lot of country and western. They’re basically turbocharged R&B songs: Black music by Black musicians. After all, Fats Domino himself famously said in 1957: “What they call rock ‘n’ roll now is rhythm and blues . . . I’ve been playing it for fifteen years in New Orleans.”

But Cochran was absolutely correct that country music was an enormous influence on a lot of 1950s rock. This is where rockabilly comes in. When Cochran says that “they kind of blended country and western music” in with blues/R&B, I assume he was talking about the first wave of rockabilly musicians. (To be fair, it’s also possible that Cochran was talking about Chuck Berry’s reworking of the country standard Ida Red into his breakthrough hit Maybellene, or to the variety of country covers by 1950s rockers like Fats Domino and Ray Charles, or to the honky tonk and western swing musicians who got pretty close to making rock music in the late 40s and early 50s on their rowdier tracks). In any event, the early rockabilly artists were primarily white musicians with more of a country music background either covering blues and R&B or at least giving a blues/R&B feeling to white “hillbilly” material.

But enough of the abstractions, lets dig into some examples!

The First Wave of Rockabilly

Bill Haley

As I briefly alluded to earlier, there are some western swing recordings from the 1940s that got pretty darn close to being rock and roll. Of the original western swing pioneers, the act that probably got the closest was Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys. Just check out Bob Wills Boogie featuring some blistering electric guitar from the legendary Junior Barnard.

Bill Haley, born approximately twenty years after Wills, picked up where that left off and fully crossed the line from western swing into rockabilly. The million dollar question is when. It’s pretty clear that Bill Haley was in full on rockabilly mode by 1954 when he and the Comets released hits like Rock Around the Clock and his cover of Shake, Rattle, and Roll.

A tougher question is whether Haley was already recording rockabilly as early as 1953’s Crazy Man, Crazy or even 1952’s Rock the Joint. Depending on your viewpoint those are either hopped up Western swing, or full on rockabilly.

Memphis: Little Junior Parker and Elvis!

The music that Sam Phillips captured in Memphis, Tennessee is another key thread in the formation of rockabilly. Sam Phillips is best known for founding Sun Records and launching the careers of Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison, Johnny Cash, and Carl Perkins. But even before any of those artists walked in the door, Phillips was capturing key blues recordings by artists like Howlin’ Wolf, James Cotton, and B.B. King. (Phillips recorded many of these artists through his related business Memphis Recording Service, for release on other labels). Some of these recordings are also essential milestones in the development of rock music–particularly 1951’s Rocket 88, which is often cited as the first rock song.

Given that background, it’s not surprising that some of (if not the) first rockabilly came out of Phillips’ studio in Memphis. In previous posts, I have argued that the first rock song is Love my Baby by Little Junior Parker and his Blue Flames, released by Sun in 1953. I think there’s an argument to be made that the song is also early rockabilly, although it’s definitely far more on the blues end of the spectrum than the “hillbilly” end.

The year after Love my Baby, Sun Records introduced the world to the man who would become the most famous rockabilly artist of all–Elvis Presley. Presley’s 1954 debut single (That’s All Right) is a foundational example of the blend of country and blues/R&B that epitomizes the rockabilly sound. Although the source material was a blues song by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, it’s hard not to hear the country influence.

Elvis’ musical fusion of country and blues continued with subsequent releases. For example, in 1955 he covered a different Junior Parker song called Mystery Train, in a version that actually drew from the guitar part in Love my Baby. Intriguingly, if Elvis contributed to the birth of rockabilly by adding a country feel to blues, you can also argue that he contributed the flip side of the coin too: by adding a blues feel to country songs. Check out his 1954 recording of Bill Monroe’s Blue Moon of Kentucky.

Rockabilly Explosion

As the flip side of Elvis’ Mystery Train (entitled I Forgot to Remember to Forget) was taking off, Sam Phillips famously “sold [Elvis’] contract to RCA for $40,000 on November 21, 1955.” Elvis’ career exploded and other labels rushed to get in on the rock craze. This resulted in a bevy of rockabilly releases.

Brunswick had a chart topper with Buddy Holly’s That’ll Be the Day. Liberty put out those innovative Eddie Cochran tracks discussed earlier. Coral Records released iconic rockabilly tracks like Johnny Burnette’s incendiary cover of The Train Kept a-Rollin‘. Capitol Records had acts like Wanda Jackson and Gene Vincent & His Blue Caps (featuring the sublime guitar work of Cliff Gallup).

Vincent and his band hit big with Be-Bop-A-Lula in 1956. Their self-titled debut album is still one of the greatest rock LPs of all time, and a great reminder that jazz and swing were an influence on early rock and roll too.

Sun Records didn’t rest on its laurels either. As noted earlier, Phillips launched the careers of Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash. He also recorded classic rockabilly tracks by lesser-known acts like Warren Smith, Sonny Burgess, and Billy Lee Riley.

Even traditional country acts like the Louvin Brothers got in on the rockabilly craze. Remember country musician Johnny Bond, Cochran’s interviewer on Town Hall Party? Not long after his interview with Cochran he released the country/rockabilly crossover Hot Rod Lincoln.

Some blues/R&B artists also contributed rockabilly masterpieces too. Listen to Tarheel Slim’s Number 9 Train, a B-side from 1958, featuring “Wild” Jimmy Spruill on guitar, Horace Lee Cooper on piano, Jimmy Lewis on bass, and John Robertson on drums. It’s one of my favorite tracks, and the flip side of the original release–Wildcat Tamer–is also killer.

Decline and Revival

Let’s go back to where we started and pick up with that interview between Johnny Bond and Eddie Cochran. Almost sheepishly, Bond says: “Eddie I’m going to ask you a question, you may not want to answer it, maybe you don’t know the answer, but I’m going to ask you anyway. . . how long do you predict that rock and roll music will stay?”

Cochran replies, “Well I think actually rock and roll will be here for quite some time, Johnny, but I don’t think it’s going to be rock and roll as we know it today.” Cochran also says, “I think it will be around for a long time but changing.”

Looking back, Cochran’s answer feels a bit eerie. The Town Hall Party interview took place on Saturday, February 7, 1959. Just four days earlier was the infamous “Day the Music Died,” when the plane carrying Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper crashed, killing all of them and their pilot. Little more than a year after the interview, Cochran himself would die in an automobile accident that also injured Gene Vincent. Cochran was just 21.

A number of other of other occurrences would stunt rockabilly specifically, and early rock and roll more broadly. Elvis was drafted. Jerry Lee Lewis’ career imploded for reasons that everyone knows. Chuck Berry was imprisoned after a controversial trial. Bo Diddley was kicked off the Ed Sullivan show for defying the host by playing his eponymous song rather than Sixteen Tons. Little Richard (temporarily) abandoned secular music for religion after, according to some accounts, seeing the Sputnik satellite and interpreting it as a sign from God.

Whether from the cumulative weight of these incidents, or from other forces, rock did change as Cochran predicted it would. As the story is so often told, the sounds of rockabilly and other 1950s rock waned, leaving a vacuum filled by the British Invasion and all else that followed. Of course, the other way of looking at it is that rockabilly never really went away, because it became an inexorable part of the rock vocabulary. After all, the Beatles covered Carl Perkins multiple times, the Rolling Stones did Buddy Holly, The Who ripped through an Eddie Cochran classic, and Creedence Clearwater Revival did Elvis doing Arthur “Bigboy” Crudup. Rockabilly songs like “Train Kept A-Rollin'” became rock standards, key repertoire for bands including the Yardbirds and even Aerosmith. (And of course, if we’re talking about the influence of fifties rock more broadly than pure rockabilly, a preposterous amount of rock and roll was built on the foundation created by Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley).

Either way, rockabilly had a revival in the 1970s. in 1977, Robert Gordon–a musician who had been associated with the New York punk scene–teamed up with 1950s guitar god Link Wray to release an excellent rockabilly album. (They would record another record together before Gordon went on to work with other collaborators on rockabilly albums at RCA). In 1979, The Clash included some rockabilly on their seminal London Calling album and Queen scored a big hit with its 1950s-styled Crazy Little Thing Called Love. The rockabilly revival rolled into the early 1980s with key releases from bands like the Stray Cats and the Blasters as well as “psychobilly” bands like the Meteors who mixed up punk and rockabilly.

Before closing out this brief history and pivoting to our DIY rockabilly project, let me briefly note that some excellent rockabilly music is still being made in the 21st century. Here’s one of my faves.

My DIY Project: The Night Wrecker

A few years ago, my wife and I were enjoying a scenic drive from the White Mountains of New Hampshire through the Connecticut River Valley. Well . . . at least we were until our car died in White River Junction, Vermont. Our rescuing hero proved to be a motorcycle-fanatic-by-day, tow-truck-driver-by-night, who took us on an hours-long, multi-state journey through the darkness to our requested dealership. That left a lot of time for conversation and we discussed weather, moose, and driving philosophy. “I don’t like to let any grass grow beneath me,” he explained, which inspired the opening lines of The Night Wrecker. A separate incident with the same car a few months later inspired the lyrics about winter weather. On that occasion, our car developed a major issue in the mountains of Western Maryland shortly before a blizzard. We were assisted by a gregarious tow truck driver who introduced himself with the line: “my name is Bull! Don’t complete it.” The Night Wrecker is a fictionalized tribute to tow truck drivers like these.

Like a lot of songs I write, the first version of The Night Wrecker basically came out as a blues. Here’s a very quick demo of the song in its original form. I intended this for my own use so it features some sloppy guitar work and bizarre vocalizations from me:

Although I wrote the song quickly, I spent a bit of time tweaking the lyrics and I eventually ditched some of the weirder ones. Like the line about sorrow and lust. . . . It rhymed, but it made our protagonist tow-truck driver sound a little unstable.

I decided to reinvent The Night Wrecker as a rockabilly track because I didn’t want to record another blues rock song so quickly on the heels of Lonesome Valentine. I also thought the subject matter would lend itself really well to rockabilly, since a lot of 1950s tracks are preoccupied with automobiles and car wrecks. The Night Wrecker isn’t a teenage tragedy song like Teen Angel, but it does imply some kind of calamity.

Speaking of calamities, check out the second version of The Night Wrecker. This was my first arrangement of the song as a rockabilly track and it is . . . out there. It sounds like a rockabilly freakout performed by a strung out combo in a film noir jazz club. The key is too high for my vocals, the arrangement is disjointed, and the production sent me teetering into manic Phil Spector territory (it was an amalgam of over 50 tracks when I gave up on it). Here it is:

I think that’s a valuable lesson for the DIY Rocker. Unless you really know what you’re doing with production (I certainly don’t), you’re much better off limiting your creation to a few tracks. I went back to basics with my final version of The Night Wrecker: vocals, electric guitar, bass, percussion.

Drums and Percussion

This is the second DIY project to feature my new tool: the Yamaha FGDP-50. For anyone who missed my last post, this is a finger drum machine that sounds surprisingly believable going into GarageBand. Since I still don’t really know how to play drums (or finger drums), I tried a couple of experiments for The Night Wrecker.

For the abandoned jazzabilly version I posted above, I recorded myself playing along on the FGDP-50 to Bill Haley’s Thirteen Women (which has to be one of the weirder rockabilly tracks with its twisted romantic fantasy about life after an atomic war).

Before the final version of The Night Wrecker, I took advantage of a Black Friday sale and purchased a Beat Buddy Mini 2 by Singular Sound. For those unacquainted, it’s basically a drummer-in-a-box guitar pedal that comes loaded with a number of preexisting loops and genres (which can be adjusted by tempo). It seems that its main intended use is for practice and live accompaniment for solo musicians. I bought it with the intention of using it as a glorified click track or a metronome-on-steroids. I found the loop and tempo that best matched my vision for The Night Wrecker, then I recorded my drum parts over it with the FGDP-50. Then I deleted the click track completely so you can’t actually hear the Beat Buddy at all in the final mix. Oh and snapping! I recorded myself snapping for sort of a King of the Road feel.

I think this is probably my most successful drum experiment to date. It’s a bit sloppy in places, which means that my fictional “drummer” sounds a bit inebriated. But I think that works with the song.

Guitars and Amps

Ah, now for the fun part: guitars and amps! Ask a guitarist or rockabilly fan to describe a rockabilly guitar and there’s a decent chance they’ll identify an orange Gretsch hollow body. The company’s guitars definitely had key adopters in the 1950s. For example, Cliff Gallup played a 1954 Gretsch 6128 Duo-Jet. Eddie Cochran played an orange Gretsch 6120. That said, my understanding is that Gretsch’s status as the default rockabilly guitar is partly a byproduct of the rockabilly revival, and its prominent use by rockabilly god Brian Setzer.

I don’t own a Gretsch (yet, mwahahahahh), so I used the descendants of two other guitar models introduced in the 1950s: a Fender Telecaster and a Fender Stratocaster. Key rockabilly guitarists like James Burton are associated with The Telecaster and the model gets a lot of love on forums about rockabilly gear. Fender didn’t introduce the Stratocaster until 1954, at which point rockabilly was already underway, but some key figures quickly adopted the model (including Buddy Holly).

I went with the Telecaster for my rhythm guitar (mixed primarily to the left channel). This is actually the first DIY Rock project featuring a Telecaster, although I’ve had one for a couple of years. For any gear heads, the one featured on The Night Wrecker is a 2023ish Fender Telecaster Ultra Luxe (set to the bridge pickup). Hopefully I’ll give that guitar a full review at some point, but it’s really a beautifully built instrument. The fit and finish are impeccable. Although a lot of Telecaster fans are purists, I like its modern touches like locking tuners, carved neck heel, and stainless, jumbo frets. The painted head stock and matching pick guard also turn heads–I’ve gotten quite a few compliments on the guitar’s looks.

I used my Stratocaster for the lead guitar (mixed primarily to the right channel) because I love its sound and it’s the only guitar I own with a tremolo arm (or vibrato arm/whammy bar). I mainly had it set to the position in between the neck and middle pickups. Where the guitar gets heavy in the refrains, I switched to the bridge position and deployed the guitar’s secret weapon–an S1 switch. You can read all about what the S1 switch does here, but in practice here it basically just thickened the sound of the guitar and increased the volume. This Stratocaster was also featured in the first DIY project. It’s an Ash American Deluxe from the 2000s. It’s the electric guitar I’ve owned the longest and it’s probably my favorite. Great workmanship, ergonomics, sustain, and tuning stability. If you want a Stratocaster, the American Deluxes from the 2000s are a real bargain on the used market. Just be aware that they aren’t the lightest Strats out there.

I used the same amp with both guitars: a Fender Hot Rod Deluxe (Texas Red), which was my first tube amp. It has more of a sixties voicing given its bell-like clean tones, but I really like how it sounds with the two Fender guitars. Besides, a lot of modern rockabilly blends in some sixties surf-type sounds anyway.

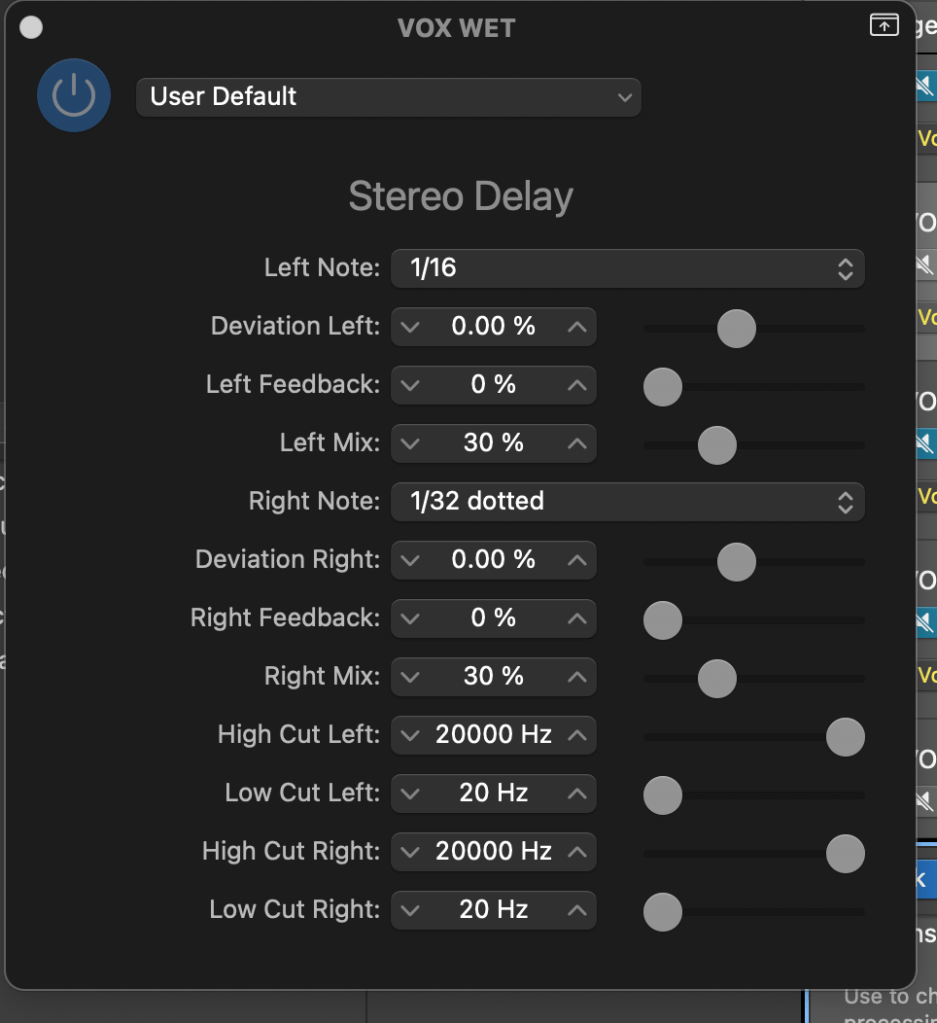

There are really only two “effects” on The Night Wrecker. First, I again used my cheap Bugera power attenuator to get a bit more saturation and overdrive out of the Hot Rod Deluxe without blowing the roof off of my house. Second, both guitars went through my MXR Carbon Copy Mini, which I set for some fifties sounding “slap back” delay. Slap back, echo, and delay are key sonic features in so much early rockabilly. My exact settings are pictured below. If you like the sound you can copy them. If you hate the sound, you can avoid!

Bass

In a perfect world, I would have used acoustic, standup bass for this project. That’s probably one of the key sounds of 1950s rockabilly. But I don’t own a standup bass and I don’t know how to play one.

So I used the same bass rig that I always do, which is pictured here. It’s a cheap Dean bass going right into Gargeband’s “60’s Combo” preset via my Focusrite Scarlett 4i4. To compensate for the fact that I was using electric bass on a fifties song, I fed it through my MXR Carbon Copy Mini with some slap back delay. It’s certainly not a true substitute for standup bass, but I think it created a vintage texture.

The bass playing on the rejected jazzabilly take of The Night Wrecker was my most ambitious to date, replete with walking bass lines. I dialed it back a bit for the final take.

Vocals

I recorded the vocals with a Sure SM58S through the Focusrite Scarlett 4i4 into GarageBand. I wanted the vocals to have a similarly retro sound to the guitars, so I added some slap back in GarageBand. I used the built in “Stereo Delay” plug in with the following settings:

Album Art

For my first time recording rockabilly, I’m pretty happy with how the final version of The Night Wrecker came out. But the best part is the album art, which I love. Full credit on this goes to my dad. (Oops, there I am breaking the do it yourself model again!). He took the photo at a glorified junkyard and edited the heck out of it in Photoshop. My goal with the lettering was to keep it simple and discrete to avoid distracting from the phenomenal photo. Thanks, dad!

Pingback: The Night Wrecker – “Live” – 2026 NPR Tiny Desk Entry | DIY Rock and Roll

Pingback: What is The First Rock and Roll Song? | DIY Rock and Roll

Pingback: I Hit the Brakes (She Hit the Beer) | DIY Rock and Roll