Read on for an adventure in exploring the roots of rock and roll with a piano and the ’66 Fender Coronado II (again)!

Oh dear—two projects into DIYRockAndRoll.com and I’m already breaking the rules. First, this project features contributions from two other musicians and one photographer. So arguably it’s not fully do-it-yourself. It’s more do-it-yourself but phone-a-friend for help. Second, and perhaps more importantly, I have been informed by the official ombudsmen of DIYRockAndRoll.com that this song is not actually even rock and roll.

Let me explain….

In my first DIY Rock and Roll project, I went back almost all the way to the start of rock and roll, to create my own surf rock. That was so fun, that I thought I should go back even further in time. To the dawn of rock and roll you say? Ha! No! Even further. I decided to recreate my own version of what American popular music sounded like right before the first rock records were made.

That meant trying my hand at 1940s Rhythm & Blues. According to Arnold Shaw, the author of Honkers and Shouters—a seminal work on the genre’s early years—”The term Rhythm and Blues came into use in the late ‘40s after Billboard magazine substituted it for race.” Shaw wrote that Billboard had used that term “since 1920 when a best-selling OKeh record of ‘Crazy Blues’ by Mamie Smith stirred the disk companies of the day to record the black female vaudeville artists, later known as the classic blues singers.”

To modern ears, a lot of R&B from that period will probably sound a heck of a lot closer to Jazz and Swing than it does to Soul or Motown, let alone Usher or Ginuwine. Let’s put on a record to demonstrate. Here’s They Raided the Joint, a 1940s classic by Hot “lips” Page:

It’s probably not surprising that this sounds like jazz, since Page actually started off as a jazz player. (In liner notes for the compilation Roll Roll Roll: The R&B Years, Dave Penny wrote that Page was on track to be a jazz star and potential trumpet rival to Louis Armstrong. Page only turned to R&B after a “commercially disastrous” move to New York City pursuant to a contract with Armstrong’s manager. According to Penny, “whether by design or not,” Armstrong’s manager “effectively defused his major client’s most potential rival.”). Even where 1940s R&B sessions are being led by non-jazz musicians, the session personnel is often stacked with jazz legends like Benny Golson.

To understand the importance of jazz in the formation of R&B, you really need look no further than Louis Jordan whose string of hits helped establish the genre. Jordan started off as a jazz player working with Chick Webb and Ella Fitzgerald and switched to R&B. He told Shaw, “I didn’t think I could handle a big band. But with my little band, I did everything they did with a big band. I made the blues jump.” Here he is in 1943:

If Louis Jordan and jazz helped give 1940s music its “jump,” other genres also coalesced to form R&B, including blues, boogie woogie, and gospel.

Why is this relevant to a website ostensibly about making rock music? Two reasons. First, R&B is itself an essential ingredient in rock and roll. Therefore, understanding the history of R&B is helpful in understanding rock. Second, there’s an argument that some R&B from the 1940s actually is rock and roll under a different name. In 1957, rock and roll pioneer Fats Domino famously said “What they call rock ‘n’ roll now is rhythm and blues . . . I’ve been playing it for fifteen years in New Orleans.”

If you’re finding Domino’s statement a little hard to believe in light of the typical view that rock started at in the 1950s, do yourself a favor and listen to one of Domino’s big influences, Amos Milburn. Here’s his recording of Down the Road Apiece from either 1946 or 1947 (depending on the source).

Listen to that pounding piano and tell me it doesn’t sound like it’s just an inch away from Jerry Lee Lewis tearing it up at Sun Records about a decade later.

Okay, okay, that’s just one example you say. What’s that you’re saying? It can’t be rock because there’s no electric guitar? Well check out the scorching guitar licks on T-Bone Walker’s Tell Me What’s the Reason from the early 1950s, many of which are virtually identical some of those later employed by Chuck Berry on Johnny B. Goode, albeit played over a smoother-edged swing. Or, go back even a couple of years earlier to 1949 and listen to Tiny Grimes’s guitar light things up around the 90-second mark on the song “Hey Mr. J B” which is so, so close to being “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.”

To be clear, I’m not trying to diminish the contributions of the 1950s rockers who are some of my all time heroes. And I actually do think the first rock song is from the early ’50s (a topic for a future post). I’m just making the case that some of the R&B of the 1940s is so, so, so close to being rock that examining and recreating it is the perfect project for a DIY-rocker.

A persuasive case for how close 1940s R&B got to being rock and roll, may be inferred by comparing the 1951 recording of Rocket 88–frequently cited as the first rock record–to Jimmy Liggins’ 1940s recording of Cadillac Boogie, which inspired it.

As a former-DJ, I could keep providing examples all day, but this is do-it-yourself rock and roll after all. So let’s take a break from the armchair musicology and turn to my DIY experiment!

My 1940s Rhythym & Blues/Jump Blues/Boogie Woogie Experiment

The Composition:

As the Rocket 88/Cadillac Boogie discussion above suggests, 1940s Rhythm & Blues and early rock and roll was a great era for songs about cars. I built this song around my spontaneous discovery that “heart breaker” and “Studebaker” rhymed. From there, the song wrote itself. Each verse plays with the themes of leaving, transportation, and insults. To hopefully keep it engaging, the distance and mode of transportation change in each verse. My protagonist starts with a Studebaker and ends up with a jalopy, interrupted only by two brief verses of bounty when he’s enjoying a Cadillac and a space ship. Don’t overthink it—I sure didn’t. I did diverge from my source material in the lyrics by including a mild swear. But it rhymed with “orbit!” I couldn’t not do it!

Musically, a lot of 1940s R&B involves instruments I don’t have access to, and can’t play: trumpets, saxophones, stand up bass… But it often features two instruments I can play—guitar, and piano. I drew inspiration from the prominent boogie woogie piano in songs like Joe Liggins’ 1950 Rhythm in the Barnyard. I picked my favorite key for piano and went with a standard blues progression—it is rhythm and BLUES after all.

I was inspired by the vocal call and response on recordings like Tiny Grimes’ 1949 recording of Drinking Beer. The backing vocals in this song are also a nod to Gene Vincent’s Pretty Pretty Baby from a few years later–a bona fide rock track that has something of a Louis Jordan feel to it. I originally recorded the backing vocals myself. That was terrible. So I called in a favor and brought on the marvelous Kay-Lettes–my mother Kay and my wife Katherine. They provided the lovely harmony backing vocals on “Pretty Baby” and “Whiny Baby.”

Anyway, DIYRockAndRoll.com is pleased to present Eight Miles Down the Road in all of its low-fi glory.

The Gear:

Guitars, Amps, Pedals:

I love the tone of early electric guitar, especially when it sounds like the guitarist was playing a little hotter and louder than the equipment could handle. (Check out Tiny’s Boogie or Little Joe’s Boogie if you want some examples).

My understanding is that the sound I’m describing is an octal tube amp breaking up. I don’t own an octal tube amp, and I’ve never owned an amp that sounds quite like one. But I did recently purchase a Junior Barnyard Pedal. That’s a boutique pedal made by Nocturne Brain and based on a Gibson EH-150/EH-185 amp. It’s designed to get exactly the octal saturation sound I wanted. (It’s named after Junior Barnard, a guitarist for Bob Wills who had a great sound and phenomenal licks). The Junior Barnyard is a key ingredient in the guitar tone on this recording. It’s coupled with my MXR Carbon Copy Mini for some delay. The amp is my Hot Rod Deluxe set pretty clean. I don’t own an electric guitar from the 1940s, so I brought out my ’66 Fender Coronado II again. Its vintage pickups work really well with the Junior Barnyard. For the solo I turned the tone knob to really dig into a burbly, vintage jazz tone.

For the playing, I’m doing my best ersatz-jazz. It’s funny… so much of the 1940s R&B guitar is probably by guys with legitimate jazz chops playing something a little more rocking. This was sort of the inverse, a guy with more of a blues/rock guitar vocabulary trying to play something a little jazzy.

Piano:

I used the only piano I own, a Weber baby grand. For the playing, it’s classic boogie octaves in the left hand. In terms of the right hand, you can maybe tell I listened to a ton of Pinetop Perkins back in the day, particularly on the chords. If I get the chance, I may re-record this song on a more period-accurate piano. My parents own an Emerson upright piano from the early 1900s. That’s the piano I learned to play on, and it’s great for boogie because decades of playing have left the action pretty easy on the hand. The Weber sounded great but wow it was a left hand workout!

I recorded the piano before I had some of my newer recording equipment so I stuck a USB mic about half way across the piano, a couple feet up, with the lid open. Honestly, I’ve never really been satisfied with my attempts at micing a piano and this one was no exception. The USB mic really didn’t capture the oomph, which is funny since I am a heavy handed pianist. Since I was happy with the playing, though, I decided to do my best to tweak the sound post-production by copying the mono piano recording and splitting and layering it across both channels to make it sound stereo. I wish I’d figured out a way to record the left and right hands separately and put each in a different channel. Next time!

Vocals, Such That They Are:

Well, there’s no getting around the fact that I can’t do Big Joe Turner, Wynonie Harris, or Roy Brown. Sigh. My “solution” was to crank the gain on my microphone and sing quietly. My ridiculous pronunciation of “Cadillac” was inspired by the phrasing of my top musical hero Ray Charles on his early Atlantic tracks like “It Should Have Been Me” and “Greenbacks.” I tried adding delay by singing through my MXR Carbon Copy Mini, but could not get it to work with this one. The vocals were just way too muddy. I ended up relying on the built-in EQ, reverb, and ambience features in Garageband.

I recorded the backup vocals at different times. I forgot to use a pop filter on my mom’s vocals and it was a big problem on the “P” in “pretty baby.” Since I wasn’t able to get her back in the “studio,” I had to resort to mixing her a bit low. I did a better job recording my wife’s vocals so she’s mixed higher.

“Drums:”

This is my second project relying on the royalty-free surf and rockabilly drum samples and patterns of Steve’s Surf and Rockabilly.

Recording Gear:

Audio Technica 2020USB (for piano, my mom’s vocals, and probably the guitar amp); Sure SM58 (for other vocals); Focusrite Scarlett 4i4; Garageband.

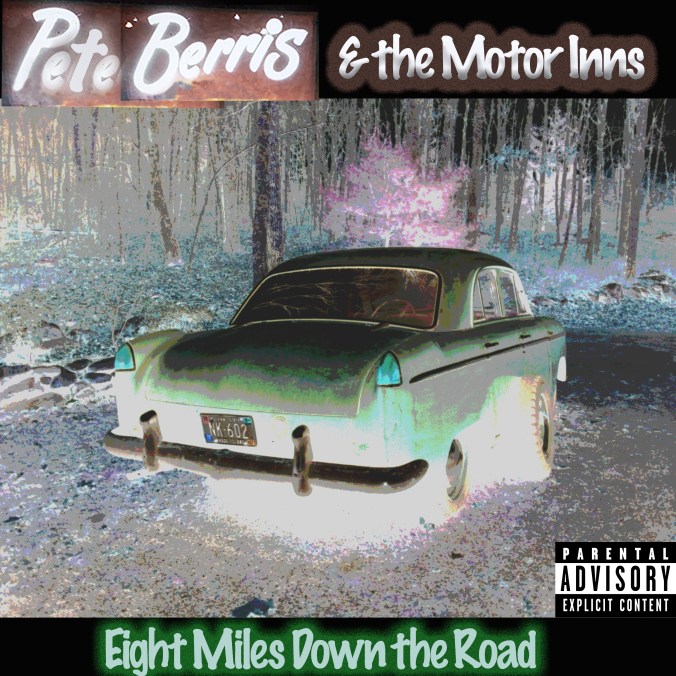

Band Name and Cover Art:

I decided to keep the same band name I used for the surf rock project: Pete Berris & The Motor Inns. More info on the background of that name can be found here.

For the album art, I wanted a picture of a classic car that would suit the lyrics. My dad provided a few options. The one I went with was his eerie, neon picture of a 1953 Willys Aero Coupe, which he used to own. At the time it was not road-worthy, making it a great match for the last verse in which the protagonist is stuck “no miles down the road” because his jalopy won’t start.

For the Lettering, I took an old photo of the neon “Berris Motor Inn” sign at night. I cropped the “Berris,” then used Photoshop to make a matching “Pete” out of letters from the sign or the closest matching font & effects I could manage. The remaining lettering is a closely matching font to the original sign, edited to have an outer neon-glow on Photoshop.

Suggested Listening and Reading:

The Arnold Shaw treatise I referenced above, Honkers and Shouters, is still probably one of the best sources for someone looking to take a deep dive into the genre and the period. It’s incredibly dense, so I’ve found it more user-friendly as a reference book. Perhaps its greatest contribution is the lengthy interviews with music legends including Lowell Fulson, T-Bone Walker, Johnny Otis, and B.B. King, as well as with a number of key industry figures of the era.

For listening, I highly recommend JSP’s 5-cd box set Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five 1939-1950. This is essential listening for fans of jazz, R&B, rock, or boogie. It’s not only historically important, but also an absolute blast. And last I checked, much of this material was not on Spotify. The Bear Family Sun Blues set would also be a great choice because even thought the music is from the 1950s, it owes a serious debt to 1940s R&B in quite a few examples, which the liner notes thoughtfully point out.

There are really so many possible entry points into 1940s R&B, but you probably won’t go wrong with T-Bone Walker, Amos Milburn, Tiny Grimes, the Liggins brothers, etc. And just because I can’t stop myself, how about some dynamite music from Helen Humes to close us out?

Conclusion:

I think 1940s R&B is often overlooked in music histories—overshadowed by the jazz that predated and overlapped with it, and by the rock, Motown, and soul that followed. If I’m honest, it took me a long time to fully appreciate the era and the genre. I found its unresolved blend of genres—not quite rock, not quite jazz, not quite blues—a bit confusing. But I think that’s what makes the music so exciting and interesting. You can feel the musical energy, forged in a mix of experimental new ideas and mastery of older ones. For the DIY rocker, making your own 1940s style R&B is a great way to hone your skills with some key ingredients of rock and roll. Just mix up some boogie piano and jazzy guitar with a strong beat and you’re well on your way.

Pingback: Do it Yourself Blues Rock | DIY Rock and Roll

Pingback: 1966 Fender Coronado II: A Profile and a Review | DIY Rock and Roll

Pingback: What is The First Rock and Roll Song? | DIY Rock and Roll